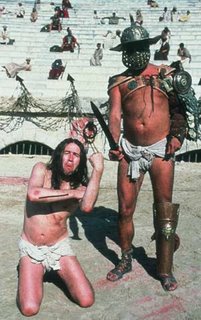

I've always been intrigued by the scenes of Middle East riot/demonstrations. You know, where impeccably dressed young men run around in a frenzy, hurling stones at government forces. It's as if they're all afraid Joan Rivers is lurking somewhere in the shadows, just waiting to ream them for their wardrobe choices. Well, somewhere along the line, this fascination led me to write the following story: Abil knelt in the sun-blistered street, his knees hard into the concrete, his shirt wet with sweat. All about him danced dark-skinned young men, their shoes skidding in the gravel, their hips jostling against his sharp shoulder blades. He heard them shout, watched them their hurl blunt projectiles into the sunlight, watched the sky blacken with rubble. Yet he was calm; he ignored it all. He ignored the chaos that clashed on all sides-- the hard faces, the flying asphalt. And instead knelt there in the street like the devout at prayer, arms outstretched, searching amongst the shuffling feet for the perfect stone.

Abil knelt in the sun-blistered street, his knees hard into the concrete, his shirt wet with sweat. All about him danced dark-skinned young men, their shoes skidding in the gravel, their hips jostling against his sharp shoulder blades. He heard them shout, watched them their hurl blunt projectiles into the sunlight, watched the sky blacken with rubble. Yet he was calm; he ignored it all. He ignored the chaos that clashed on all sides-- the hard faces, the flying asphalt. And instead knelt there in the street like the devout at prayer, arms outstretched, searching amongst the shuffling feet for the perfect stone.

His calloused hands crept along in the rubble, grasping first a chunk of splintered concrete, then a sand-smoothed stone. Yet even though he crouched there, low to this task, his back bent like an old man's, his eyes were ever up. Never straying from the shadows at the far edge of the courtyard. His hands, you see, were well accustomed to their work; he left them to it. They knew the line of a well-shaped stone, the heft of one which might fly true. His hands were confident, and his eyes were needed elsewhere-- across the courtyard. For there, in the shadows of a long abandoned tenement building, in its shallow furrow of coolness, stood row upon row of heavily-armed soldiers. The enemy.

Abil was not afraid. He was not intimidated. Instead, he simply sat there on his haunches, eyeing the squadrons from within the teeming crowd. He knew that these forces would stand there for hours, idle, holding their ground. Their shields at chin level, their dark mirrored visors cloaking any trace of humanity. Knew they would wait as long as it took. Patient for the sun to fall and prod the angry crowd, tired and weary, home. There was no hurry. The soldiers knew that the ill-equipped rioters could do them no harm, they lacked the firepower. Indeed, most of the hurled rocks fell pathetically short of their targets. Merely skipping amongst their ankles like wind-whipped locusts, brushing shoe tops or plunking feebly off armored shins. And they also knew that if a youth grew brave, if one crept close enough for any real danger, a well-placed rubber bullet would certainly halt him.

These boisterous youths were really only frisky pups, they knew. Rambunctious, a bit out of hand sometimes, but harmless. And they also knew that any action against them stronger than a swat across the nose might bring the only thing they truly feared: the news cameras. So they waited, patient, as still as the stone columns that lined the boulevard.

Abil felt his left hand snare a promising stone, pull it close. Then he glanced down. He quickly counted the arsenal he had gathered between his knees: several well-rounded cobbles, a handful of sharpened bits of concrete, three halves of brick. Good enough.

He spat into his palms and rubbed them together. The dust that swirled in the heat and gathered on his fingertips could make a perfect throw go awry. And that would not be acceptable. Each stone had a purpose, each stone must ring true. So he spat again into his palms, rubbed them clean. And when he was satisfied, he wiped them on the cuffs of his pants, stood.

Looking down, though, he noticed that the dust had, almost at once, began clinging again to his hands. He sighed. It was always the way. No matter where he found himself. In any number of cities, on any of a thousand sweltering afternoons. There was always the dust. Swirling about him like a pestilence, blotting out the sun.

It seemed sometimes that the dust was the only common thread in his long march of days. The dust and the struggle. The faces of his fellow rioters changed from fight to fight, as did each strange language they barked into the dry air. He'd stood in the Gaza Strip with Palestinians all about him, hurling stones at the Israeli army. Then, years later, at their own police force. He'd stood shoulder to shoulder with Hezbollah. Hamas. The P.L.O. With any number of lesser known factions. He'd rioted in Jordan, in Egypt. Thrown stones in Syria, Turkey, the Golan Heights. First on one side of the government, then the other. And had long before lost interest in keeping track of the differing camps, of the grievances. Instead, all he noticed was that the dust kicked up by the expensive shoes of his companions, that crept into their silken shirts, it was always the same. Always rising slowly into the hot heavy air like quick lime, forever coating his tongue.

It was as if the dust was connected to all of it, somehow an integral part of every skirmish. As if it somehow strung his days together like a child's daisy chain. Perhaps if there was no dust, he sometimes pondered, there would be no struggle. No shouts of fury, no hurled stones, no hatred. Yet, he knew it was silly to think of such things. Pointless. There was no escaping the dust. At each demonstration it rose billowing into the air, higher and higher as the mob's fury gained momentum. Stinging the eyes, the throat. Permeating everything.

He coughed once, picked up a stone. And there, towards the western flank of the stern line of soldiers, spied a target. An inexperienced youth, perhaps, certainly one on his first assignment. From across the courtyard Abil's sharp eyes noticed the soldier had not properly arranged his bullet-proof vest. It lay askew, off his left shoulder. Leaving his left collarbone dangerously exposed. So he gathered himself, hefted his stone. Then launched it into the swirling dust.

He watched it arc across the courtyard, black and swift as a sparrow. And, just before it struck, he allowed his eyes to begin a slow scan down the ranks. He did not need to witness it strike its target. He knew the outcome, he knew his aim was true. Instead, he set about finding his next target. And because of this did not see the young soldier crumple, fall to one knee. Then get dragged backward by his fellows, into the mass of black guards, on his way to the infirmary. Instead, he merely notched an invisible tally in his head and scanned on.

One thousand, he whispered to himself for encouragement, one thousand and the afternoon was still young. It was the accepted rate: one thousand US Dollars for each soldier he sent to the hospital. The next day's paper would confirm the final tally. It was the rate he had received for years, the one he had accepted at countless such altercations. Yet the men who compensated him came from many groups, held many beliefs, followed many prophets. In fact, many of them were sworn enemies. It seemed this was the one they could all agree upon: one thousand US Dollars. Well, and also that whenever such measures were needed, whenever such force was called for, run of the mill rioting was no longer enough.

The news crews, you see, had long grown immune. They disregarded the well- dressed youths hurling asphalt that had once been deemed newsworthy, ignored the burning cars that once drew them like moths. They simply looked the other way. What was needed now was a body count. Of any sort. If not the newsmen would never drag themselves away from their air-conditioned lounges, from their Pernod and cigarettes. If not the riot would never be seen or heard. And since weapons were hard to come by and, even if they were used, the repercussions so harsh, something else was needed. That something was Abil.

So he was shepherded, from city to city, country to country, on such occasions. If news coverage was necessary, Abil was there. Standing faceless in the raging crowd as if he was one of them, picking off careless soldiers with his miracle arm. He could hit a saucer from one hundred meters away, and often did so for new interested clients. Could send upwards of fifteen soldiers to the infirmary in the span of an afternoon. It always piqued the media's interest when seemingly unarmed street youths could do this. And, as Abil's agent always told his clients, if they were lucky, if Allah smiled on them that day, such casualties might anger the rest of the standing force. Send them, in a rage, barreling into the rock-hurling crowd. With truncheons and rubber bullets. And then, perhaps, they might even make CNN.

Yet despite all his successes, despite all the money he'd made, Abil still felt unsure of himself. He felt empty. He had no real beliefs, held no people sacred. He was merely a prostitute. Selling his arm to the highest bidder, damn the ideology. He'd thrown stones with the PLO and then, years later, at them. And felt nothing. Either way.

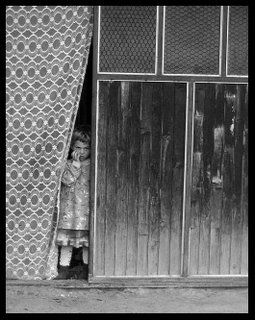

Sometimes, though, when he was in a foreign land, in bed alone in a darkened room, he wished it were different. Wished he could somehow feel the fire he saw in the faces around him, perhaps know the strength of conviction it took to rage so. Maybe then he might be able to sleep at night. Maybe then he might know peace.

Yet, in the end, such serenity never came. He knew it was hopeless. For how could he embrace any of the ideologies he found himself aiding, how could he rally behind the abuses claimed? All about him were young men in silken shirts and gold chains, thousand dollar shoes and salon clipped hair. Most even looked as if they'd merely been on their way to the discotheque when they happened by the violence. Where was the oppression when such extravagances could be afforded? What were the abuses? The grievances?

Sometimes, in fact, he found himself looking sideways at these privileged young men beside him. Eyeing the hatred in their gazes and wondering to himself if such passion was not misplaced. If it was not simply hatred for the sake of hatred. Despising the government or rival religions merely because that was the way. Because that was how it had always been. Well, how could he embrace such views? He often asked himself. How could he support such ideas?

He could not. It was the answer that always came. He was not one of them. He was not one of any of them. He was, instead, alone. As he had always been. Merely traveling the Gulf, sometimes smuggled across borders in livestock transports, sometimes in car trunks. Hoarding the money he received so that he might one day retire to a quiet port city, away from it all. Away from such hatred. Perhaps then find something in which to believe.

Once, though, a couple of years back, Abil's agent had come with a rumor that had been whispered to him in a darkened bar. A rumor that sparked in Abil a notion that his lonely travels might be, at last, coming to end. That, perhaps, there was some something else at which his arm might succeed, away from the dust and the struggle. It seemed a rich American had heard of Abil and his wondrous arm, had heard of him and wanted him for his own. Now, precisely what this rich American had in mind Abil was not so sure. His agent had mentioned many things-- a certain national pastime, and a sports team, and millions of dollars. But to Abil it was all merely a mystery. All he knew was that the task he was needed for was in the United States. And that was enough.

Abil, you see, had watched many movies about the United States. And in all those movies there had never been any of the swirling dust that plagued his dreams, not one pinch. It seemed a magical place. The air was clear, the sky azure blue. There was no dust and, therefore it seemed, no hatred. And so for weeks he lay awake in his narrow cot, far into the night, dreaming of his new life. Wondering what it was he would do in America, what he was wanted for. Certainly he would not hurl stones. Surely there was no need for such things there. There was no dust and, therefore, no struggle.

Over the weeks stories drifted to Abil of cases upon cases of caviar being sent to consulates, to embassies. Even Prime Ministers. All from his wealthy suitor. Abil had consorted with terrorist groups, he knew this was the reason, his name was on many lists. His emigration, therefore, would be difficult. And the caviar was supposed to grease the wheels of diplomacy, produce the necessary Visa. Or perhaps, if all else failed, generate a set of high quality forged papers. "Anything," this mysterious fellow had been overheard saying, "just get me that goddamn arm."

Eventually, though, word came that it was not to be so. That all of the rich American's gifts had gone for naught. The caviar had been thoroughly enjoyed, but Abil was still a danger. A great one. He could not be allowed to emigrate. Abil was disappointed, yet he held no grudge. America was a wondrous place, this he knew. And they certainly could not risk corrupting it by allowing in such a sinister, empty-souled youth.

Abil coughed once into his shoulder, spat. Then picked up another stone. Across the way there, in the shadows, a soldier had turned his back for a moment. He appeared to be talking to a companion behind. A painful error. One he would probably never repeat. Abil saw the exposed elbow, sheathed only in the canvas of his thin regulation coat. He grinned shallowly, with little satisfaction. And, as the stone leapt from his hand, as it arced across the dazzling blue, only one thought crept its way into his head-- one thousand Dollars. It was the only thing that drew his attention away from the dust, and from the hollowness of his heart.